Illustrations by Jason S

Science of the Supermarket: An Analysis of Consumerism in the Developed World

“This should be enough.” The woman casually handed me four one hundred-dollar bills in exchange for two carts brimming with groceries. I stood there in sheer disbelief while simultaneously trying to fathom how she could have possibly spent that much. As I continued my career as a ShopRite cashier, I recognized that she was not an anomaly. I distinctly remember orders taking ten minutes to pack, being handed several hundred-dollar bills in a single transaction, and overflowing tills that warranted multiple collections within a single shift. To entertain myself, I counted how many orders cost more than my week’s salary (nearly all of them) and mentally tracked how many exceeded two hundred dollars. . . three hundred dollars. . . four hundred dollars. The initial shock may have worn off, but the curiosity about the factors that cause people to spend exorbitant amounts of money on groceries persists. The lucrativeness of a supermarket is the result of achieving the “Golden Mean,” the harmonious balance between satisfying producers’ sales expectations and maintaining a high level of customer loyalty that largely results from layout, sensory experience, and soundscape. In equilibrium, these forces have the power to blur the line between food needs and wants to the point where they become nearly indistinguishable.

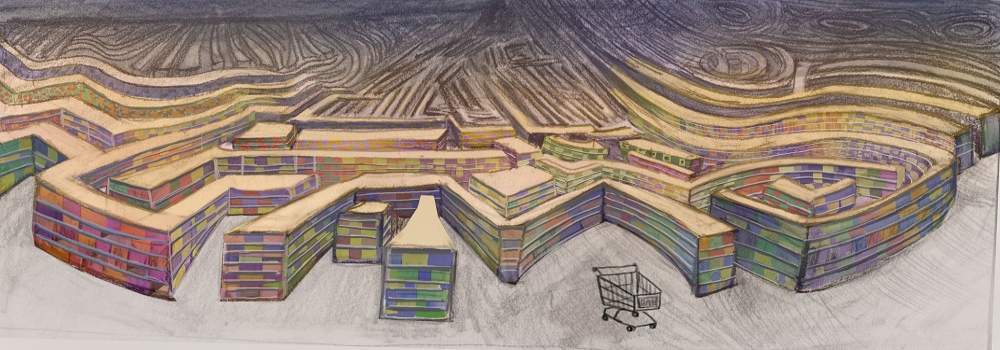

The trite phrase, “location, location, location” describes management’s objective when calculating how best to organize their own spatial real-estate, from the large-scale layout to individual shelving. Essentially, this knowledge and application is the key to maximizing sales and can only be deeply understood by studying where shoppers naturally gravitate and placing products accordingly. While a producer may find it tempting to turn the supermarket into a labyrinth of isles and sections, Marketing Consultant Peter Boros and colleagues suggest modeling the supermarket in a way that “maximizes the shortest traveled path” (27).

Moreover, the consumer seldom travels the full length of the isle, consequentially leaving the vast majority of the store uncovered.

By capitalizing on convenience, management can encourage superfluous consumption by placing products directly in the traveled path of a consumer. This practice simultaneously heightens shopper loyalty as it prioritizes efficiency, which consequently maintains the Golden Mean. Optimization of this route is investigated through Radio Frequency Identification, a tracking software that reveals unconventional movements of the typical shopper in addition to fourteen common paths. Research finds that shoppers do not tend to weave up and down isles, since this plan of attack is often too inefficient to be seriously considered by the time-conscious. Moreover, the consumer seldom travels the full length of the isle, consequentially leaving the vast majority of the store uncovered. Management must recognize these nuances in order to capitalize on the observable paths the consumer already frequents, instead of attempting to lure them off-track. Herb Sorensen, a Ph.D. in marketing and creator of the Radio Frequency Identification system, refutes the notion that the consumer can be easily veered off-course by a product they had no intention of buying, and in turn asserts that “we need to see where the customer goes in the store and select appropriate merchandise to place there, not expect them to come to the product” (35). In other words, management must deliberately place items in the path of the consumer; it cannot be expected that they stumble upon what they wish to buy. Failure to recognize this principle and act accordingly demonstrates an imbalance of distribution and attraction. The unhindered access to a product is essential in order to begin the viewing, which should lead to shopping, and ultimately buying.

Furthermore, uninhibited special real estate heavily contributes to consumer satisfaction, as it alleviates distraction that prevents a sale in the short-run and continued patronage in the long-run. Access is a crucial—and more or less uncontrollable—variable that must be present in order for sales to occur. Though it seems obvious that a product needs to be within reach in order for purchasing to be possible, there are many more implications than one would expect pertaining to shopper migration and positioning. To ensure that the product is attainable, “management should aim to ensure constant movement through the store by providing permanent stimuli” (Luck and Benkenstein113). How does one control the flow of hundreds of independent customers? To what extent can these efforts be effective in creating a calculated movement of the masses? As it turns out, these are less questions of logistics and more of physiological inquiry. Lack of access is largely accredited to confusion and an (often unwanted) emotional response. If a person exhibits confusion regarding any aspect pertaining to the sale—the price, the premise of the produce, the positioning—they will delay their purchase, and instead occupy space that another consumer may wish to inhabit. The same can be said about an emotional response. The solution for curtailing the irrational behaviors of a consumer is to move items that may elicit confusion or an emotional response to a less-frequently trafficked area, which fosters an evenly dispersed flow of traffic throughout the retail space. Since up to 80% of buying decisions are made directly at the point-of-sale or right in front of the shelf, calculated macro-level positioning has the ability to deter or facilitate a sale (qtd. in Luck and Benkenstein 104).

Furthermore, individual shelves can be arranged to maximize profits depending on the target consumer for that particular product. The most expensive products tend to be directly at eye-level so that rushed shoppers mistakenly toss the costliest options into the cart without a second, economical thought. It is important to note that the effectiveness of the eye-level pricing is not guaranteed; if the product displayed is Lucky Charms, “the shelf just below the middle one is ideal” for a sneaky child riding by in a shopping cart. Clearly, “if you want children to touch something, you must only put it low enough, and they will find it. In fact, objects placed below a certain point will be touched by children only” (Underhill 144). To increase customer satisfaction, supermarket employees often “block” the merchandise by literally moving remaining goods to the front of each shelf to create the appearance of bountiful offerings. While this activity seems trivial, the illusion of choice and tidiness through “merchandising display techniques [and] location…reveal[s] that consumer perception of store performance on these attributes determines retail patronage” (Marques et al. 18). Essentially, if a customer believes that a store is well-stocked and organized, two positive outcomes arise: their likelihood of making an impulsive purchase increases because of high product availability; and their likelihood of a second trip increases under the guise that the store is well-managed, thus resulting in gains to their utility.

The issue with this, however, arises amongst regular customers and their increasing familiarity with a layout.

Contributing to a slight imbalance of the Golden Mean, anchor departments and other larger points of interest—consisting of produce, meat, dairy, and bakery—are “traffic builders and thus are dispersed for the convenience of the owners and managers—not really for the convenience of shoppers” (Sorensen 35). Often located at polar ends of the store, they help insure that a larger area of the store is covered, instead of the paltry 25% of the retail area that is typically trafficked (qtd. in Sorensen 32). The typical, strategic placement of anchor departments ensures that the customer’s traveling path is maximized in a way that is not blatantly obvious or downright irritating. Two more distinct layout situations are identified: twenty-seven shopping-tasks or “clusters” house specific needs, such as pet care or paper goods (Boros et al. 27); and the “racetrack” that lines the perimeter and can accurately be equated to a shopper’s home-base (“Tag Team”). The racetrack, primarily consisting of refrigerated goods, dairy, and meats, is a permanent fixture that serves as a retreat for many customers. It is not unusual that, “…every supermarket follows a similar layout with fruit and bread usually placed at the front of the store and frozen products placed towards the end of the route” (Hynes and Manson 172). The issue with this, however, arises amongst regular customers and their increasing familiarity with a layout. These twenty-seven clusters then become subject to rearrangement. Thus, the pursuit to find a can of whipped cream or a bottle of ketchup becomes increasingly more challenging, and the profit-maximizing layout is reset once again. To maintain the equilibrium of the Golden Mean, management should avoid frequent, drastic change that could seriously reduce customer satisfaction. From a shopper’s perspective, the layout must facilitate their timely, routine dash around the store; distractions like bulky end-caps or a crowd of other patrons should be mitigated. In essence, the balance exists between the two parties through gradual adjustments that add value to the experience by prioritizing the consumers’ convenience, which indirectly results in profitability.

Attention to the servicescape is a relatively new phenomenon for this sector, but one that is undoubtedly crucial to orchestrating a sensory experience and keeping pace with growing competition. The term “servicescape” can best be described as the “result of a complex mix of environmental dimensions: (1) the ambient conditions (temperature, air quality, noise, music and others), (2) the space/function (layout, equipment and others) and (3) the signs, symbols and artefacts (signage, personal artefacts, style of decor and others)” (Marques et al. 20). Within the last decade, “the grocery retail sector has undergone intense change” by leaving the sterile, odorless aesthetic of a conventional supermarket back in the sixties (Marques et al. 17). The emergence of grocers like Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods, which promote a distinct, naturalistic image, encourage enhanced design of a traditional market’s major hubs, namely the bakery, deli, and produce section, in order to meet the demands of an increasingly capricious public. Shoppers equate a traditional supermarket’s curation of a carefully designed servicescape with their desire to remain competitive. They become more inclined to shop at this retailer in the future, as stores continuously evolve by prioritizing new consumer demands.

Psychologist Paco Underhill observes that consumers now partake in “cross-shopping” (Marques et al. 17), or frequenting different establishments to meet specific needs. To combat this lack of loyalty, a quality servicescape is no longer a trivial component that can be overlooked by management, but rather a necessity. In order to compete with the emergence of niche markets, heavy advertisement and the conscious design of particular spaces is essential to creating parallels between a supermarket’s department and those of their rivals. Gluten free, natural foods, and organic sections have begun to emerge amongst the familiar chains. In the produce section, signage detailing the origin and harvesting methods bears a striking similarity to that found in higher-end stores. With the rise of atypical markets reducing the patronage of the conventional marketplace, there is a pressure to mimic the servicescape of an alternate retailer as much as possible in order to make the experiences more comparable. Management’s observable dedication to fostering a comparable, sensory shopping experience in an average supermarket promotes the Golden Mean, as customers are more encouraged to buy impulsively due to heightened emotional response.

Underhill aptly coined the term “sensual shopping” to characterize the wants of the consumer and detail the all-encompassing sensory experience that has been concocted at the turn of the decade. He notes that the consumer is subject to a positive experience upon entry: “most good [supermarkets] now feature on-premises bakeries, which fill the air with warm, homey scents. You may be in the vitamin section when that aroma hit you, and before you know it you’ve followed the olfactory trail right up to the counter” (Underhill 164). The mundane weekly trip is not only more enjoyable, but stimuli are employed as a vehicle for increasing impulsive purchases. If the flowers are arranged and are conveniently placed near the entrance—whether they are housed in the interior of the store or are lined up along the exterior—the consumer who is initially hit with a fresh floral aroma will be more inclined to pick up a $2.99 Potted Mum for Mom at the start of their trip than if the floral department is buried deep within the store. The same principle can be extended to the bakery or the fragrant rotisserie chickens in the meat department..

Again, the Golden Mean is achieved through striking the balance between upholding a high aesthetic composition while remaining fully functional. During my brief stint as a cashier, I was inundated with the elderly population’s complaints about their inability to read a certain sign or reach goods placed on the top of an elegantly crafted seasonal display. While signage and displays may have been aesthetically pleasing and fit the theme at hand, any attempt to heighten the aesthetic composition is pointless, and ultimately detrimental, if it detracts from the convenience factor. Controlling atmospherics can prove to be a difficult feat since no specific “target market” exists for a conventional supermarket–all members of the public will frequent the establishment. In turn, any aesthetic decisions must be deliberate and expertly executed in order to appeal to as many as possible. By prioritizing functionality, supermarket atmospherics are beneficial to both the customer and manager by promoting efficiency and facilitating sales.

To a consumer, the soundscape is often overlooked in comparison to more obvious design elements. Yet it is an integral part of the shopping experience that can promote excessive consumption or hinder exorbitant purchases by eliciting an unforeseen psychological response. Quite simply, management should strive to facilitate “organized sound” (qtd. in Hynes and Manson 173). The subtle background music that wafts through the store proves to be the “atmospheric variable readily controlled by management” which is subject to the highest degree of manipulation (Milliman 86). Ronald E. Milliman, who holds a Ph.D. in Marketing, suggests that music is selected to “improve store image, make employees happier, reduce employee turnover and stimulate customer purchasing” (86). His investigation of musical dimensionality focuses extensively on cadence, whether it is a deviation in tempo or an adjustment in volume, and its effect on the following: pace of store traffic flow, daily gross sales, number of shoppers expressing an awareness of the music (Milliman 87). Surprisingly, his findings reveal that the difference between no music and slow tempo music, or no music and fast tempo music, is marginal when examining both the pace and sales volume. The major discrepancy, however, lies in the difference between the slow tempo music and the fast tempo music. Daily sales reported over the span of nine weeks averaged $12,112.35 with the fast-tempo beats, whilst slower-tempo music yielded sales of $16,740.23 – a difference of 4,627.39 or 38.2 % in sales volume (Milliman 90). The evidence supports the psychology that music has a positive, direct impact on “one of the most important parts of the approach behavior, namely purchase” since slower music encourages slower movement around the store, allotting more time for the shopper to peruse the isles, survey the vast product offerings, and make impulsive purchases (Andersson et al. 559).

From a producer’s perspective, increased sales are indicative of successful operations–in the short run, that is. Marketing Researcher Pernille K. Andersson and colleagues warn that manipulating the “servicescape” for short-term gains may jeopardize long-term gross sales (559). While consumer “attitude,” opposed to “behavior,” fuels short-term sales, long-term growth is fueled by customer satisfaction and loyalty. In other words, the producer who inundates the customer with uncomfortably slow-paced music that contributes to an unsatisfactory experience risks losing their patronage entirely. This clear imbalance of the Golden Mean exemplifies the importance of selecting a soundtrack that is both appropriate for the establishment and pleasing to the demographic at hand.

Furthering the idea of appropriateness, management must make educated decisions that cater to the subconscious desires of their clientele. Niki Hynes and Struan Manson, in their essay “The Sound of Silence: Why Music in Supermarkets is Just A Distraction,” note that “one manager reported that the music was used to meet customer expectations: ‘they like to hear something in the background’” (175). However, simply playing something to fill the void, rather than orchestrating a soundscape that is enjoyable to the consumer, demonstrates a clear underutilization of resources. Music is something that remains “in the background of the shoppers’ perceptual fields,” which proves why attempts to understand that perceptual field, or the thoughts and concerns of the consumer, is even more worthwhile (Milliman 90). Andersson and colleagues further explore the psychology of the consumer by dividing their study by gender and focusing on each sex’s reaction to the tempo.1 They found that females prefer slow or no music at all, while men favor an upbeat tempo (559). This conclusion can provide a logical explanation to the noted differences in revenue, since women are the primary shoppers at grocery stores and the ones enjoying slower-paced soundtracks, which results in a majority of shoppers who enjoy longer trips (Andersson 559).

The typical lilting elevator music or the occasional classical piece often characterizes a supermarket’s soundscape, but the rustling of bags, incessant beeping of registers, or the grinding of the cart wheels on a linoleum floor are forgotten contributors to the distinct cacophony. Soundtrack is more often than not viewed as a single variable subject to manipulation, rather than a composition of noise. Hynes and Manson stray away from planned music assumptions, and veers towards examination of the aleatory sounds—a restless child’s shrieking, machinery, alarms, and the like—and a consumer’s conscious reaction. This critical approach to analyzing the “overall sonority” of the space highlights discrepancies between reactions to different categories of sound (Hynes and Manson 172). While many patrons reported indifference towards mechanical noises, they expressed deep dissatisfaction for human sound.

Theoretically, the Golden Mean operates like an economic equilibrium, one that balances the desires of producer and consumer to a perfect point of intersection, but one could argue that this model is far too idealistic to be observed in supermarket setting. From this perspective, the supermarket is an engine that fuels corporate greed, masked by the necessity of food. There is no need to design a store with the consumer in mind because management is fully aware that their goods will be consumed in any economic condition. People need to eat; toying with arbitrary factors such as layout, aesthetic appeal, and atmospherics is an inconsiderable allocation of time and resources.

While the opposition’s argument contains some validity, the Golden Mean is imperative for profit maximization; there is a considerable difference between simply maintaining operations and generating a profit. Without considerable attention to layout, servicescape, and soundscape, or extreme manipulation of those characteristics, both parties are at a considerable disadvantage. The producer may see a decrease in sales if the consumer feels that the producer has crafted an ordeal that is merely a laudable push to buy more, as opposed to an enjoyable experience. It is evident by the current rise of competitors that consumer satisfaction is inexplicitly linked to experience or “shopper marketing” (“Free Mug”). This somewhat ambiguous yet all-encompassing terminology suggests that capturing the consumers’ attention through any means possible, from price breaks to life-style campaigns, is increasingly important in a technological age defined by choice. With this sudden diversification of food retailers, management must be “proactive” rather than “reactive” in accommodating the shopper. The looming threat of Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods and the supermarket’s cross-shopping clientele has become too great to ignore. Conclusively, “grocers and other retailers that refuse to do so are making a mistake” (“Free Mug”). Failure to cater to the consumer and their capricious nature will only undermine the success of conventional supermarkets in the developed world.

Upholding the Golden Mean is a complicated yet thoroughly rewarding feat that ensures profitability and satisfaction for both the consumer and producer. The deliberate manipulation of layout, aesthetic elements, and soundscape will, if done correctly, ultimately spur impulse buying. Despite the efforts to increase revenue, these elements can also bring novelty to an otherwise mundane weekly activity. By arranging the store in such a way that essential items occupy polar opposite spaces, management can create a slightly convoluted “revenue maximization path” while also applying Sorensen’s theory of bringing the product to the consumer. Likewise, management can opt for more tasteful ambiance, complete with stimuli that will coax the buyer into purchasing the products that they literally experience. The soundscape is crucial for dictating the speed of the shopping trip, but the symphony of sounds—both the controlled and uncontrolled variables—should be carefully monitored in accordance with the shoppers. Thus, the Golden Mean fosters a harmonious relationship between two parties whose needs are largely dependent on the fulfillment of the others’ in order to prosper.

[1] Although it should be noted that her study is conducted in a home electronics store in Sweden, her research and design study reference Dr. Milliman, thus rendering the experiment relevant since it provides expansionary information to pioneer findings in supermarket soundscape research.

Instructor: Professor Frank Hilson

What do food selection, preparation, and distribution tell us about people? What insight does food provide into the politics and mores of a community, culture, or country? This honors English 110 course, “You Are What You Eat: Food and Culture,” used food as a mechanism to examine our society and our world. Courtney Zozulia and Patrick Reyes’ culinary journey began with an exploratory in-class workshop where they investigated a topic of personal interest. (This food concept became the foundation for their research paper.) The idea was then discussed in a five-page exploratory essay, which was later fine-tuned during a one-on-one conference with the instructor. Several more workshops helped to round out their discussion. The students’ arguments were then showcased in a five-minute PowerPoint presentation where they received input from their peers during Q & A. Courtney’s essay investigated the cleverness with which western supermarkets entice consumers to buy food (and more food than needed) in “Science of the Supermarket: An Analysis of Consumerism in the Developed World.” Patrick took a global look at food, or lack thereof, in “A Greater Price to Pay: Poverty and Food Insecurity,” addressing the plight of the poor and their access to proper nutrition. Overall, they spent about two months brainstorming, researching, composing, rewriting, and editing to produce two insightful essays.

Works Cited

Andersson, Pernille K, et al. “Let the Music Play or Not: the Influence of Background Music on Consumer Behavior.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 19.6 (2012): 553-560. November 2012. Web. 4 April 2016.

Boros, P?ter, et al. “Modeling Supermarket Re-Layout from the Owner’s Perspective.”Annals of Operations Research. 238 (2016): 27-40. Web. 5 April 2016.

“Free Mug with Purchase: Retailers and Manufacturers Ramp Up ‘Shopper’ Marketing.” Knowledge@Wharton. Wharton University of Pennsylvania. 16 February 2011. Web. 2 May 2016.

Hynes, Niki, and Struan Manson. “The Sound of Silence: Why Music in Supermarkets Is Just a Distraction.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 28 (2016): 171-178. Web. 4 April 2016.

Luck, Michael, and Martin Benkenstein. “Consumers between Supermarket Shelves: the Influence of Inter-Personal Distance on Consumer Behavior.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 26 (2015): 104-114. Web. 4 April 2016.

Marques, Susana H, Gra?a Trindade, and Maria Santos. “The Importance of Atmospherics in the Choice of Hypermarkets and Supermarkets.” The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research. 26.1 (2016): 17-34. Web. 4 April 2016.

Milliman, Ronald E. “Using Background Music to Affect the Behavior of Supermarket Shoppers.” Journal of Marketing. 46 (1982): 86-91. Web. 4 April 2016.

Sorensen, Herb. “The Science of Shopping.” Marketing Research: A Magazine of Management & Applications. 15.3 (2003). Web. 5 April 2016.

“Tag Team: Tracking the Patterns of Supermarket Shoppers.” Knowledge@Wharton. Wharton University of Pennsylvania. 5 June 2005. Web. 2 May 2016.

Underhill, Paco. Why We Buy: The Science of Shopping. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999. 144-163.