Illustrations by Sarah Muldoon

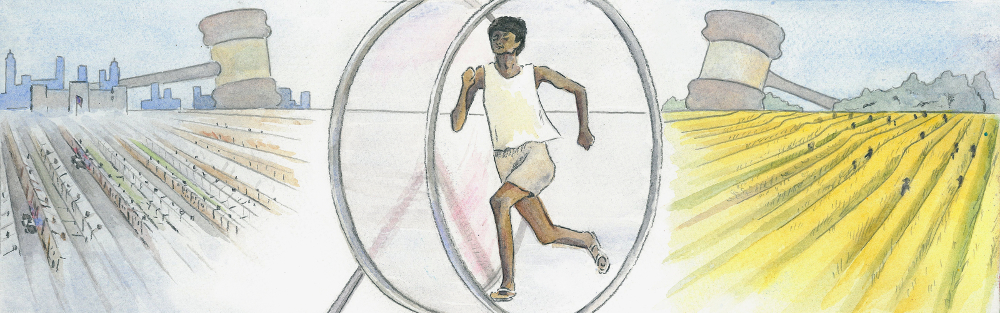

Separate But (Un) Equal: Education of Slaves in the Antebellum South and Blacks in America Today

As Americans, we have long endeavored to erase and forget the horrible stain of slavery that has soiled the fabric of American history and culture, and we have sought to make reparations for centuries of abuse and injustice. In this attempt to make amends, legislation like Brown v. Board of Education, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and affirmative action programs have been designed to relieve the residual effects of a time in our history where injustice and discrimination were well within the mainstream and ingrained in the letter of the law. Unfortunately, current data on the achievement gap between African American and White students in the United States suggest that the legacy of slavery and discrimination in America persists to the modern day, raising alarm for the present necessity to fight for equality of education for all.

Hailing from a moderately wealthy suburban White town, I am a firsthand witness to the endemic resegregation of schools in the United States that squanders the quintessentially American hallmarks of diversity and multiculturalism in public schools. Just a short trip from my house in White suburbia, is a far less privileged and far more urban city where White students are a significant minority in public schools. Despite the minor separation in distance, there exists a major rift in income, race distribution, and public school performance between my small middle class town and its neighboring city. The state of Connecticut in general is a perfect example of this disparity seeing as the state houses one of the richest counties in the country, with extraordinarily wealthy towns like Greenwich a short distance away from destitute cities like Bridgeport. The public school systems in these areas mirror these socio-economic trends and leave African Americans struggling to keep up with White students, facing much greater adversity in education. For this reason, I have chosen to examine two interrelated matters: 1.) the ways in which the legacy of slavery and Brown v. Board of Education have impacted modern education, and 2.) the parallel between the historic legal denial of educational opportunity for slaves and the scarcity of opportunity for quality education for African Americans in the modern era.

Slaveholders in the Antebellum South made no secret of their intentions to suppress the education of African Americans by explicit laws outlawing the teaching of slaves to read and write. While early Northern slaveholders, especially Puritans, taught slaves to read in order to indoctrinate them into Christianity, in the South, this practice was strictly forbidden. In South Carolina and Georgia, legislators “set the tone for the South” by passing legislation to “suppress teaching slaves to read and write” through the imposition of a “twenty-pound fine on anyone instructing a slave in reading and writing” (Neufeldt 7). In South Carolina, this offense also came with a six-month prison sentence for Whites teaching slaves to, read or severe whippings for slaves or freed Blacks engaging in the same activity. One South Carolina legislator, J. Wofford Tucker, justified such measures on the grounds that they help to ensure that “every white man shall feel that he is a freeman, and every negro know that he is a slave” (qtd. in Watson 7). Slaveholders and non-slaveholding Southerners alike felt it was necessary to distinguish slaves and Whites through suppression of slave education. This practice allegedly helped to dissuade Southerners of the abolitionist cause and prevent slave rebellion. Slaveowners were fearful that educating slaves would make them dangerous by “making the slave more conscious of his or her status and perhaps awakening a desire for more knowledge and a higher status” (Neufeldt 5). This fear was especially felt in the early 1800s after news came of slave rebellions in Hispaniola, and Nat Turner’s Rebellion in 1831 (Neufeldt 7). Also, as Octavia Butler points out in her neo-slave narrative Kindred, another reason that it “was against the law in some states to teach slaves to read and write, was that they might escape by writing themselves passes” to leave their plantation on a supposed errand, and some even “did escape that way” (Butler 49). Slaves could potentially write themselves a series of passes that would allow them free passage all the way to the North, or forge their own free papers. All of these laws resulted in slaves being unable to eat “of the tree of knowledge” because the “tree was guarded by the flaming swords of wrath, kept keen and bright by the avarice and cupidity of the master class” (Miller 3,4). This system of mental oppression, which was accompanied by the more conspicuous physical oppression of slaves, “stunted and dwarfed” the minds of slaves and degraded them, resulting in abhorrent crimes against humanity (Miller 10). For this reason, the oppression of slave thought by slaveholders was possibly more destructive and unjust than physical beatings and involuntary labor.

The vast majority of slaves, whatever their potential may have been, were kept ignorant and subservient under the slave system in the Antebellum South. This kind of suppression of talent and potential can be seen today in the state of African American education in modern America.

One may contend, in contrast to the claim that slave education was suppressed, that slaves were, in fact, given some education as skilled craftsmen, and that some slaves were educated in literacy regardless of the laws of the time. It is true that “plantations, in particular, depended on slave craftsmen” (Neufeldt 4). There were “various incentives” for slaveholders to “train slaves in the crafts,” including the increase in value of a trained slave, and the opportunity for slaves to do year-round work as opposed to only seasonal work in the fields (Neufeldt 5). Slaves could be trained as slave blacksmiths, carpenters, or seamstresses in addition to the traditional role as field hand or domestic servant. Despite the opportunity for this kind of training, these slaves did not have their minds expanded in the way that reading and writing could have improved their mental faculties. These slaves were merely granted a very narrow skillset in a particular profession. Moreover, slave owners only allowed for this kind of training because they knew that it would not lift the condition of slaves as literacy threatened to do. The men who trained slaves in these crafts were the same who argued that slaves could never be granted the “facilities of intelligence and communication, inconsistent with their condition, destructive of their contentment and happiness, and dangerous to the community” (Watson). One may make the argument that some slaves were still able to become educated despite the laws of the time. For example, Olaudah Equiano was able to become educated as a slave and go on to write an autobiography years later when he became free. Equiano could become literate and “read the scriptures” of the Old Testament and “hear the word preached” despite his status as a slave on board a ship (Equiano 179). However, these cases tended to be scarce in the slave system, as few examples like “the literary taste of Phylis Wheatley, the scientific acumen of Benjamin Banneker, [and] the persuasive eloquence of Frederick Douglass” were allowed to develop in the face of ongoing efforts to suppress their voices and minds (Miller 10). The vast majority of slaves, whatever their potential may have been, were kept ignorant and subservient under the slave system in the Antebellum South. This kind of suppression of talent and potential can be seen today, in the state of African American education in modern America.

In 1954, in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the Supreme Court under chief justice Earl Warren declared that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” a departure from the ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 which allowed states to segregate their school districts, leaving Black schools lagging noticeably behind. Brown v. Board of Education declared that schools must make efforts to integrate, increasing their diversity and ameliorating the status of African American education, which was poor compared with White education at the time of the ruling. Despite the intentions of the Supreme Court ruling, the effect of Brown v. Board of Education has been underwhelming due to a lack of enforcement, and subsequent decisions have undermined the desegregation effort. According to Michigan State University professor Laura McNeal, the “current educational milieu suggests that Brown has made more of a symbolic as opposed to a substantive impact on school integration.” This is due largely to the cases that succeeded Brown v. Board of Education like Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell in 1991, Freeman v. Pitts in 1992, and Missouri v. Jenkins in 1995. In Board of Education of Oklahoma City v. Dowell, the decision was made that “court-ordered busing mandates could be eliminated” when “those districts have made a good faith effort to attempt all practical measures to eliminate segregation” (McNeal 566). This enabled schools that had made some progress in desegregation to stop busing students from underprivileged areas, a policy meant to achieve diversity in public schools. The implication of the ruling was that schools could give up on their desegregation efforts if they had made some improvement. In the case of Freeman v. Pitts, it was ruled that “where re-segregation is a product not of state action but of private choices, it does not have constitutional implications” and that “it is beyond the authority” of the “federal courts to try to counteract” any “demographic shifts” which worked to resegregate schools (McNeal 566, 567). This case absolved the federal courts and schools of responsibility for counteracting the de facto (non-legislative or social) discrimination that occurs in housing trends where Black and White families tend to separate into different neighborhoods based on relative wealth and therefore enroll in separate schools. States no longer had to make efforts to integrate schools in the face of rapidly segregating communities. Missouri v. Jenkins also worked to harm desegregation efforts by further defining the “point in which a school district may be released from a court desegregation order” (McNeal 567). More and more schools were being exempted from legislation meant to increase diversity, and standards for integration were being lowered.

A comprehensive study in 2003 showed that “72% of African American students attended “predominantly minority” schools that were 50% to 100% minority” and “17.8% of African American students attended “apartheid” schools that were 99% to 100% minority” where the minorities specified were Black and Latino students

The failure of the courts and schools to enforce the desegregation order in Brown v. Board of Education is supported by modern statistics on the status of school integration. A comprehensive study in 2003 showed that “72% of African American students attended “predominantly minority” schools that were 50% to 100% minority” and “17.8% of African American students attended “apartheid” schools that were 99% to 100% minority” where the minorities specified were Black and Latino students (Smith 27). A 2011 study by the US Department of Education confirmed that this massive resegregation has only persisted: “on average, White students attended schools that were 9 percent Black while Black students attended schools that were 48 percent Black” (Bohrnstedt et al. 1). Schools in America are rapidly resegregating in large part because housing trends have segregated communities across America. Blacks tend to be of lower socio-economic status than Whites on average, which means that many live in poorer, predominantly Black communities. These communities then have schools that are seriously underfunded due to low tax revenue from the impoverished community. This trend is most dominant in suburban areas because “despite a huge increase in minority students in suburban school districts, serious patterns of segregation have emerged” causing “many of the most rapidly resegregating school systems since the mid-1980s” to be those located in suburbs (Smith 26). This can be attributed to the fact that communities in the suburbs are increasingly segregating, fueling this disparity in ethnic representation in schools. Resegregation trends are greater in the North than in Southern schools, and in both the North and South, schools are more segregated now than in 1988 (Smith 26).

The significance of the resegregation of schools is that it is a major contributor to the achievement gap in education between White and African American students. The evidence for this achievement gap comes from analysis of factors like performance on standardized test scores, which is an accepted measure of academic success. According to the US Department of Education, on the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) exam in 2011, on the Mathematics Grade 8 Assessment, “Black students scored 31 points lower, on average, than did White students,” and this gap is especially shocking when considering that “the difference between NAEP Grade 8 mathematics Basic and Proficient achievement levels is 37 points” (Bohrnstedt et al. 3). This puts Black students at nearly an entire achievement level below White students on average.

There exists a very close link between the achievement gap between Black and White students and socioeconomic status, both differing greatly between the two groups. Existing evidence shows that the “college-completion rate among children from high-income families has grown sharply in the last few decades” compared with the “completion rate for students from low-income families” which has “barely moved” (Reardon). This is because wealthier students attend schools with better resources, better teachers, have less domestic problems, and are likely exposed to violence and drugs at lower rates. The resegregation of schools has increasingly left Black students in poor districts with underfunded schools, causing them to achieve at lower levels compared with White students in majority White schools. This is evidenced by the fact that, according to a 2011 study, “83 percent of Black students” in schools that were predominantly Black were eligible for free or reduced school lunch programs compared with “53 percent of White students” in predominantly White schools (Bohrnstedt et al. 14). These discrepancies in economic status are clear indicators of academic performance and suggest that many African American students are struggling to compete with wealthier White students. This correlation is further proved by the fact that “throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s until 1988” when the amount of Blacks in predominantly White schools “peaked at 43%, there was a substantial decline in the Black?White achievement gap” (Smith 28). Then as “desegregation plans were dropped and resegregation began to increase in the 1990s, the achievement gap began to grow again” (Smith 28). This trend serves to prove that the actions of the federal courts indirectly led to the shrinking and then growth of the achievement gap when desegregation efforts were abdicated by the courts. The lack of federal enforcement of Brown v. Board of Education after 1988 and the string of court cases in the 1990s that disarmed desegregation efforts (Oklahoma City v. Dowell, Freeman v. Pitts, and Missouri v. Jenkins) clearly damaged Black student achievement and widened the achievement gap.

Evidence of a discipline gap which is correlated to the achievement gap further reinforces the idea that resegregation negatively affects the achievement gap. The fact that Black students attend lower quality schools in more impoverished and crime ridden areas contributes to their receiving disproportionately more suspensions. According to the Children’s Defense Fund “black students were two to three times overrepresented in school suspensions compared with their enrollment rates” across the nation (Gregory et al.). These students are alienated as troubled students and miss class time due to their higher rates of suspensions. This can be attributed to the fact that their schools are situated in low income areas where violence and drugs are far more common. These schools likely do not have adequate resources to reach out to students in troubled situations and are more likely to give up on these students, trapping them in a cycle of misconduct and low performance. Further, these students have a much less positive outlook due to their schools’ low graduation rates, and they have less motivation to study hard in school and stay out of trouble. This all helps to explain why students in lower performing, predominantly African American schools fall behind their more privileged White counterparts.

Arguments may be made against the claim that resegregation is the primary factor in the rise of the achievement gap. There is some evidence to suggest that external factors outside of the discrepancy in school quality and funding for minority schools may be affecting the achievement gap. For example, African American students are less likely to have one parent with a high school degree or higher compared with White students (Bohrnstedt et al. 14). This disadvantages them, as they are less likely to receive education in their home from their parents. Also, the fact that “the income achievement gap is already large when children enter kindergarten” suggests that other external factors affect students’ academic performance outside of school quality (Reardon). One explanation for this initial gap is the fact that in lower income households, which may be disproportionately Black, children come into kindergarten with smaller and less sophisticated vocabularies. It may not be entirely the fault of these segregated Black schools that African Americans underperform their potential. There also exist examples of extraordinary students who have come out of very poor minority communities and have been extremely successful. One prominent example is Richard Sherman, the San Francisco 49ers cornerback who went from an extremely poor high school in Compton California to go onto college at Stanford and then the NFL. However, these cases defy the general trend in education in America and tend to be extraordinary exceptions.

Despite the existence of other potential factors that contribute to the achievement gap, it is clear that the segregation of White and Black students into unequally funded schools plays a major role in the underperformance of African American students in modern America. Black students in America today suffer from a severe lack of opportunity to receive quality education. In some ways, the situation can be compared to that which existed when slaves were denied legal education in the Antebellum South. In both instances, legislators exhibited reckless disregard for the condition of African Americans, and at times sought intentionally to prioritize White education. The main difference in the education of slaves in the Antebellum South and African Americans today is that slaves were explicitly denied education, and the teaching of slaves was outlawed in many areas. Modern African Americans instead suffer from a scarcity of quality education. The indubitable result, in both instances, is the existence of an African American population underperforming their true potential, faced with greater adversity than their White counterparts.

The legacy of slavery and the case of Brown v. Board of Education have greatly impacted modern American education, leaving African Americans with less opportunity for quality education, reminiscent of the denial of educational opportunity to slaves in the Antebellum South. From a modern perspective, it is difficult to believe that in a nation founded on the principles of freedom and opportunity, legislation in the Antebellum South could have explicitly denied African Americans the basic right of access to education. Even though we would like to believe that the days of slavery are dead and gone, we seem to be repeating many of the same mistakes of our past.

Instructor: Professor Frank Hillson

My research project provides the inquisitive and motivated student an opportunity to investigate any topic which strikes his or her fancy, as long as it is approved by the instructor. The topic generally emerges from a personal interest or perhaps a desire to investigate an intriguing concern, but it must satisfy four basic requirements: is it researchable, is it arguable, is it significant, and is it likable. This last query highlights the large amount of time and effort (approximately two months) the writer will spend on composing, drafting, and editing a researched argument of approximately 10 pages. Hopefully, it should be a pleasurable, albeit challenging, writing experience. Daniel Scanlon picked an educational issue concerning African-Americans, which impacts our entire nation. His idea grew out of material in our Honors E110 course: The Slave Narrative: Past and Present.? He found a problematic area?the current educational discrepancies between black and white student achievement?which, he argues, stems from educational practices (or lack thereof) in the antebellum South. John Bachman-Paternoster was piqued by a medical issue based on a poignant personal example. He further researched this topic and built his research paperAntibiotics and Superbugson keen data and examples of the potential catastrophe, which the over prescription and misuse of antibiotics could cause to humanity. Both authors wrote insightful and significant pieces in an engaging and convincing voice.

Works Cited

Bohrnstedt, G. et al. School Composition and the Black?White Achievement Gap?, NCES 2015-018. U.S. Department of Education, Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, 2015, http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch.

Butler, Octavia E. Kindred. Beacon Press, 2003. Print.

Equiano, Olaudah. The Life of Gustavus Vassa? The Classic Slave Narratives, edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. First Signet Classics Printing, January 2002. pp. 31-225. Print.

Gregory, Anne, et al. “The Achievement Gap and the Discipline Gap: Two Sides of the Same Coin?” Educational Researcher. 39.1 (2010): 59-68. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/27764554.pdf.

McNeal, Laura. “The Re-Segregation of Public Education Now and After the End of Brown V. Board of Education.” Education and Urban Society. 41.5 (2009): 562-574, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0013124509333578.

Miller, Kelly. From Service to Servitude. Ed. Lawrence Cremin. N.p.: New York: Arno, 1969. 3-47. Print. American Education- Its Men, Ideas, and Institutions.

Neufeldt, Harvey G, and Leo McGee. Education of the African American Adult: An Historical Overview. New York: Greenwood Press, 1990. Print.

Reardon, Sean F. “The Widening Income Achievement Gap.” Educational Leadership. 70.8 (2013): 10-16, http://www.ascd.org/publications/educationalleadership/may13/vol70/num08/The-Widening-Income-Achievement-Gap.aspx Smith, G P. “Desegregation and Resegregation After “Brown”: Implications for MulticulturalTeacher Education.” Multicultural Perspectives. 6.4 (2004): 26-32, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1207/s15327892mcp0604_8?needAccess=true.

Watson, HL. “The Man with the Dirty Black Beard: Race, Class, and Schools in the Antebellum South.” Journal of the Early Republic. 32.1 (2012): 1-26, http://muse.jhu.edu/article/465878.

Paper Prompt

My research project provides the inquisitive and motivated student an opportunity to investigate

any topic which strikes his or her fancy, as long as it is approved by the instructor. The topic

generally emerges from a personal interest or perhaps a desire to investigate an intriguing

concern, but it must satisfy four basic requirements: is it researchable, is it arguable, is it

significant, and is it likable. This last query highlights the large amount of time and effort

(approximately two months) the writer will spend on composing, drafting, and editing a

researched argument of approximately 10 pages. Hopefully, it should be a pleasurable, albeit

challenging, writing experience. Daniel Scanlon picked an educational issue concerning

African-Americans, which impacts our entire nation. His idea grew out of material in our

Honors E110 course: The Slave Narrative: Past and Present.? He found a problematic area?

the current educational discrepancies between black and white student achievement?which, he

argues, stems from educational practices (or lack thereof) in the antebellum South. John

Bachman-Paternoster was piqued by a medical issue based on a poignant personal example. He

further researched this topic and built his research paperAntibiotics and Superbugson

keen data and examples of the potential catastrophe, which the over prescription and misuse of

antibiotics could cause to humanity. Both authors wrote insightful and significant pieces in an

engaging and convincing voice.