Illustrations by Erin Erskine

The Ethics and Aesthetics of Photojournalism

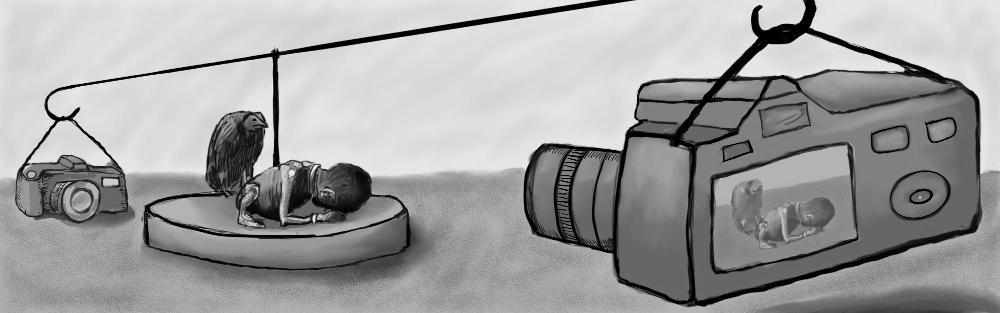

The way in which we tell a story has evolved as technology has progressed. Before there was language, there were drawings on cave walls. Then came written word, and eventually, we arrived at photography. Photography has revolutionized communication and the means by which we convey and share information. It has become very easy for anyone to take a photograph and share it with the world. There are, however, specific practices of professional photography, one being photojournalism and another being fine art photography. Photojournalistic images are meant to be unedited and real, while photographic art allows for the editing and manipulation of pictures. Often times, powerful images produced as a result of photojournalism or art tend to display themes of pain, suffering, and even violence. When do these images become exploitive, and is there really a difference between photojournalism and art? Both practices attempt to inform viewers of a certain event with the hope of also making the viewer feel something towards the event it is portraying. While photojournalism may be exploitive, this exploitation is not always unethical and sometimes even necessary in creating an image that is both beautiful and impactful. This allows for photographs to reveal truths about human activity and humanity as a whole, as well as encourage compassion and reflection within viewers.

The line between photojournalism and photographic art is sometimes hard to locate. Photojournalism is often very documentary in nature with little to no intention of being creative, but rather informative and raw. According to the NPPA (National Press Photographers Association), the primary goal of visual journalism is to provide?faithful and comprehensive depiction of the subject at hand,? and to report on significant events and varied viewpoints (?Code of Ethics?). The photographs taken may reveal great truths, expose wrongdoing and neglect, inspire hope and understanding and connect people around the globe through the language of visual understanding? (?Code of Ethics?). The NPPA recognizes, however, that the images may also cause harm if they are harshly intrusive or manipulated (?Code of Ethics?). Therefore, they put forth a code of ethics in order to hold their journalists accountable. The code is meant to encourage visual journalists to keep their work as ethical and truthful as possible with rules like: Treat all subjects with respect and dignity. Give special consideration to vulnerable subjects and compassion to victims of crime or tragedy. Intrude on private moments of grief only when the public has an overriding and justifiable need to see? and Editing should maintain the integrity of the photographic images’ content and context. Do not manipulate images or add or alter sound in any way that can mislead viewers or misrepresent subjects? (?Code of Ethics?). Never in their mission statement or code of ethics does it indicate artistic portrayal or beauty as a goal of photojournalism. David Finkelstein, author of Photojournalism,? suggests that ?[p]hotojournalists at their best produce visual references that illuminate human activity, reveal our vices and virtues, and offer iconic representations of events and individuals in a manner that can be read? by as many as possible? (Finkelstein 108). Again, there is an emphasis on revealing truths about humanity but no mention on the role of art and aesthetics within these photographs. Informing the public seems to be the main purpose of photojournalism, but at what point does it become a form of art

Figure 1: Sebastiao Salgado, Sahel: The End of the Road

Figure 1: Sebastiao Salgado, Sahel: The End of the Road

Sebasti?o Salgado is a famous photojournalist who is well known for his photographs of migrants and refugees being too beautiful? (Kimmelman). Therefore, it is possible for photojournalism to be considered aesthetic. A problem that arises with photojournalistic images being beautiful is the idea of aestheticizing pain? (Anstead). Chris Vogner, a Nieman Fellow from Nieman Reports, comments on the idea of aestheticizing: I?ve always been puzzled by the idea of aestheticizing pain. I?ve heard other people criticize various works of art for that very thing, but it?s a complaint that I?ve just never quite understood. Maybe it?s the word aestheticizing.? I always thought of it as a way of processing horrible things? (Anstead). The above photograph from Salgado?s book, Sahel: The End of the Road, shows an African woman and her children walking in the desert during a drought and war-stricken time period. Compositionally, the photograph is undoubtedly beautiful, but you can see the starvation clearly from the ribs and shoulder blades protruding from under their skin. His photographs are of those who have been pushed out of their villages in hope of survival, and so it is likely that this woman and her children have been trekking the desert in search of safer place. Is this image exploiting them, or, as Vogner suggests, is it a means of processing the tragedy? Can it be both

While people complain that this photograph, as well as Salgado?s many others, are too beautiful, meaning they exploit the people he captures, Michael Kimmelman of the New York Times reveals, Of course his photographs are exploitative. Most good photojournalism is.? The idea of most good photojournalism? being exploitive may be argued against, but even the NPPA recognizes that photographs can be intrusive. They warn photographers against being harshly intrusive,? but the fact remains that exploitation is sometimes intrinsic to good? photojournalism because the primary goal is to share important truths that the photographer feels the public should know about. If the ends justify the means, meaning if the exploitive photograph is of something crucially worth sharing, then the image has value and is considered good.? Thus, the intrusive aspect is overshadowed by the importance and potential impact the image holds. The impact the photograph has may even be a direct effect of the exploitive element. It was one thing to try to wake humanity up to suffering in the world via photographs from the early years of the last century through the golden age of photojournalism in the 1940’s and 50’s, when most people saw distant places and learned of faraway disasters through photographs,? Kimmelman writes, but it is another thing to try to do so now, when the number of images that flash across television and computer screens diminishes the value of any single image you may see.? Therefore, since the number of media that we see every day has increased greatly over the years, photographers now struggle to make a picture have a lasting effect. The images are an aid in processing horrible events, while also trying to encompass a deeper meaning and extend it to the public. There is a battle between remaining ethical while still producing powerful images, and so the concern for ethics may be lost to a profound message that lies within the picture. Creating a beautiful aftermath photograph is important not only for processing trauma, but for also impressing upon a viewer an impact that lasts much longer than the time they took to look at it.

For both photojournalism and photographic art, a huge motivation for producing photographs is to initiate conversation, and if not conversation, at least spark compassion. Paolo Pellegrin, another world famous photojournalist, published a book containing pictures of conflict zones, As I Was Dying, in which he removed the captions from his photographs and put them at the end. Pellegrin explains the rationale of his work:

I think the way this book is constructed, and also the way in which photography has to offer something as a language, is so as to have inside of itself the echo of something larger ? what I call a metaphor. And I think by taking away a part of the information, which in this case is the caption, you in a way push (or force even) the viewer to engage ? if you want ? in a different or more profound conversation with the pictures? (Lane 63).

Figure 2: Paolo Pellegrin, As I Was Dying

Figure 2: Paolo Pellegrin, As I Was Dying

Pellegrin attempts to create pictures that contain something which is unfinished or untold,? and the viewer is encouraged to see them, not only as documentation of historical and political events, but also as a testimony to a different level of shared experience? (Lane 64). This is an important line between basic documentary photojournalism and more artistic photojournalism. Not only does the journalist want to construct photographs that reveal truths about important events to the public, as is the essential goal according to the NPPA (?Code of Ethics?), but he also wants to create an experience for the viewer, as most artists strive for when sharing their work. An experience is something that personally affects your life, and so rather than just creating a great photograph that is nice to look at, he also wants it to personally touch you in some way. Documentary photojournalism is not nearly this ambitious. The mere goal is to inform, but with Pellegrin?s photographs, he wants to produce an experience. Pellegrin admits the images ultimately speak about an extreme human condition, one where people are in conflict zones and struggling between life and death, but they are also pictures of hope, courage, and a man?s will to live: ultimately I certainly feel a sense of compassion, which I hope the viewer will also feel. And so these are the emotions that I would like ? that I hope ? the viewer might in some way or other feel themselves to be touched by, through the experience of looking at this book and these pictures? (Lane 64).

Another important characteristic of Pellegrin?s photographs that transforms his work from documentation photography into artistic photography is the fact that he manipulates his pictures to add drama to them, as indicated by the exaggerated contrast in Figure 2. While his pictures appear to follow traditional requirements of news photography, like working in black and white, they all have a very deliberate pictorial ambiguity? (Lane 63). His impression of vagueness is enforced by his decision to keep the captions separate from the images. This careful and directed execution of his work causes it to be considered more so art rather than documentary photojournalism, since documentary photographs are not meant to be edited or manipulated in any way so as to not detract from the truth? of the image.

Raw documentations of disaster may be the acceptable form of photojournalism in order to ensure trust in the media, but it is certainly not the only form of photojournalism that reveals truth

Raw documentations of disaster may be the acceptable form of photojournalism in order to ensure trust in the media, but it is certainly not the only form of photojournalism that reveals truth. While edited images can skew the reality of the situation, they allow the photographer to focus on specific elements of a picture that may lead to a deeper truth that would have been missed out on had the image remained untouched. This is where photojournalism and photographic art overlap, and it is important that they do so, since, like Kimmelman said, images are starting to have less and less effect on people, and therefore, elements of beauty are essential to hold our attention. Unfortunately, people tend to find suffering beautiful, as evident from Kimmelman?s point, Two thousand years of Christian art is based on the premise that of course suffering can be beautiful.? Tim O?Brien?s How to Tell a True War Story? explains the beauty that can be found amongst horror and violence and how the truths? of a disaster are not always clear. O?Brien reveals,

The truths are contradictory. It can be argued, for instance, that war is grotesque. But in truth war is also beauty. For all its horror you can?t help but gape at the awful majesty of combat. You stare out at tracer rounds unwinding through the dark like brilliant red ribbons. You crouch in ambush as a cool, impassive moon rises over the nighttime paddies. You admire the fluid symmetries of troops on the move, the harmonies of sound and shape and proportion, the great sheets of metal-fire streaming down from a gunship, the illumination of rounds, the purply orange glow of napalm, the rocket?s red glare. It?s not pretty, exactly. It?s astonishing. It fills the eye. It commands you. You hate it, yes, but your eyes do not. Like a killer forest fire, like cancer under a microscope, any battle or bombing raid or artillery barrage has the aesthetic purity of absolute moral indifference?a powerful, implacable beauty (77).

The appalling scenes that photographs tend to display repel us while simultaneously drawing us in. Like O?Brien said, it is simply astonishing ? the image fills you with awe and horror, leaving you feeling as though you just bore witness to something really beautiful, powerful, and important in uncovering certain truths of humanity.

While edited images can skew the reality of the situation, they allow the photographer to focus on specific elements of a picture that may lead to a deeper truth that would have been missed out on had the image remained untouched. This is where photojournalism and photographic art overlap, and it is important that they do so

While there is something a little unsettling about the fact that humans find appeal in horror, and that photographers use it as an opportunity create a beautiful picture, the ultimate question that remains is whether or not these pictures are ethical. In trying to answer this question, is it not important to consider how the people whom the photos are depicting feel about them? Susan Sontag makes a very interesting point regarding the victims? thoughts about these images: ?[They] did want their plight to be recorded in photographs: victims are interested in the representation of their own sufferings. But they want the suffering to be seen as unique? (Sontag 87). Of course, one group of people?s sufferings is not equivalent to another?s and it would be wrong to portray it as so. To portray it all, though, is not explicitly wrong, and it may even be welcomed. People want their story to be told, and they want it to be told in a unique? way. The beauty that photographers like Salgado and Pellegrin add to their images make the victims? stories stand out. Is that not what they want? If we cannot help them, should we not at least acknowledge, and maybe even reflect and show compassion? Having their struggles recorded in photographs helps people to remember them and their experiences. Remembering is an ethical act, has ethical value in and of itself,? says Sontag, That we are not totally transformed, that we can turn away, turn the page, switch the channel, does not impugn the ethical value of an assault by images. It is not a defect that we are not seared, that we do not suffer enough, when we see these images?Such images cannot be more than an invitation to pay attention, to reflect, to learn, to examine the rationalizations for mass suffering offered by established powers?All this, with the understanding that moral indignation, like compassion, cannot dictate a course of action? (91). Therefore, just because we do not jump to action or experience a profound change every time we see a tragic picture does not mean we cannot reflect, examine, and question what we are looking at. It is impossible for a person to act on every sad thing they see in the world, so the next best course of action is to learn and attempt to understand. This is not to understand in any literal sense, because no one could ever begin to understand someone else?s sufferings, but just to observe respectfully. As long as we remain ethical in the way we view photographs, then the photographs themselves are ethical.

A lot of pressure and responsibility is put on photographers and consequently, so is a lot of critique. There is pressure to be ethical, while also to be as informative and truthful as possible. And yet, people still complain about aestheticizing suffering,? when it is those very people who find the suffering beautiful. They are photographs of real people in real situations, and photographers are just doing their job when they pick up their camera and capture that moment. They deliver to us beautiful, haunting, informative, truthful, horrific, meaningful, profound images, and so what we do when we view them is just as important. Do not look away, do not pass over it in indifference. In this modern world, the way in which we view photographs has almost become as essential as the way in which they are taken and displayed. Photojournalism and photographic art often become one, due to the idea that viewers require something more powerful than the typical black and white news cover photo. The viewers are a driving force behind this shift towards more aesthetic images, just as they are influential on the ethics of exploitation in photography. As long as we remain engaged observers who are willing to consider, reflect, and learn, then the ethics of a photograph are upheld. There will be endless debate about the morality of photojournalism, but one thing is clear: no matter the manipulation, aestheticism, and exploitation, it is an image of real people and their realities, and viewers must always be mindful of that.

Instructor: Professor Ida Stewart

In my Spring 2017 composition course, Disaster and Aftermath: Making Sense of the Senseless,? we analyzed literature and other rhetoric that engages with disasterpersonal and collective traumas from the September 11 terrorist attacks to school shootings to racial violence?and we considered the poetics and ethical challenges of memorial art that draws meaning from discord, pursues understanding, and attempts to unify diverse and fractured communities. Our writing and discussion explored what writers and other artists have to say about terror and trauma, and also how they say it?how a text?s genre and form/craft/rhetorical elements can variously shape the writer?s and reader?s understanding of the subject matter. We observed surprising trends related to experimental narrative structure and shifting points of view, and we grappled with ethical tensions and limitations in the relationships among writers/artists and their subjects. Ultimately, we developed new understanding not only about disaster, but also about the transformative power of the written word. We found that good writing?including successful English 110 papers?doesn?t always yield answers, but rather more and better questions.

Works Cited

Anstead, Alicia, et al. Art and Trauma– And Journalist as Observer.? Niemann Reports, Winter 2009, http://niemanreports.org/articles/art-and-trauma-and-journalist-as-observer/. Accessed 14 May 2017.

Code of Ethics.? NPPA, https://nppa.org/code_of_ethics. Accessed 14 May 2017.

Finkelstein, David. PHOTOJOURNALISM.? Journalism Practice, vol. 3, no. 1, 2009, pp. 108-112, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17512780802560823. Accessed 14 May 2017.

Kimmelman, Michael. PHOTOGRAPHY REVIEW; Can Suffering Be Too Beautiful The New York Times, 13 July 2001, http://www.nytimes.com/2001/07/13/arts/photography-review-can-suffering-be-too-beautiful.html. Accessed 14 May 2017.

Lane, Guy. The Art of Photojournalism.? The Art Book, 31 October 2008, pp. 63-64, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-8357.2008.00995.x/abstract. Accessed 14 May 2017.

Pellegrin, Paolo. As I Was Dying. Dewi Lewis, 2007.

Salgado, Sebastiao. Sahel: The End of the Road (Series in Contemporary Photography). University of California Press, First Edition, 11 October 2004.

Sontag, Sonia. Regarding the Pain of Others. Picador, 2003.

Paper Prompt

Explore a specific problem, conundrum, or predicament related to the ways we talk, write, or think

about disaster? in contemporary American culture. Research and write your way toward resolution

of a very specific question about this problem. Know that resolution? need not be an answer?;

?resolution? might be a better understanding of the nature of the problem.

I encourage you to root the paper in some personal curiosity, question, or obsession. The essay

?Magnificent Desolation? by Elisa Gabbert may be a good model for how to interrogate your own

curiosity and use it as a springboard.

Here are some examples of the types of problems you might explore:

? How soon is too soon To what extent can humor help a trauma survivor heal?

? What can we learn about 9/11 by studying political cartoons from the weeks following the

attack?

? Why did I feel disappointed when the hurricane was weaker than expected? To what extent do I

desire disaster? How and why?

? How does the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina redefine the word scar

Research the ongoing scholarly conversation about the topic. Engage with information from sources

to inform and develop your own ideas throughout the paper. Use your paper to contribute to the

ongoing conversation.